The Heart of Libertarianism is a Love for Your Neighbor and for Justice

By Ryan Lindsey

Our core beliefs and convictions should translate into a worldview, and (if you feel inclined to be civically engaged) that worldview should mold and shape your ideology. Too often though, it’s the other way around – our political ideologies shape our sense of morality and personal philosophies. This has certainly been the case for me at times in my life, and is still a bad habit that is easy to get sucked into.

Maybe it’s the visceral nature of modern politics, the desire to fit in with our families and friends, or the inherent hesitation most of us share to admit when we’re wrong. For whatever reason though, nothing good comes from adhering to any political ideology that you have not arrived at as a result of a thought-out and considerate worldview. Once we begin doing that, a tribal, us-vs-them mindset is inevitable. No matter our good intentions, once tribalism takes hold we begin simply trying to rack up points – what we accomplish is irrelevant so long as “we” win and “they” lose. We trade important ideological achievements for small, technical team victories (and let me tell you, when it comes to victories, libertarians don’t have much to brag about).

For me to properly and fully explain the ins-and-outs of the particular brand of libertarianism I subscribe to, I believe I should first explain my worldview – after all, that’s where my ideology comes from. Maybe some of what I say will be relatable for you, but maybe none of it will. Everyone’s journey to the libertarian ideology (or whatever other ideology you practice) is different. If nothing else though, I hope that you will reflect on your own ideology and (if needed) reevaluate how you got to this point.

Early Beliefs

Like the majority of libertarians, I was not raised in a household that was in any way libertarian. Born and raised in Southwest Missouri during the 90s and early 2000s, I was surrounded by Republican partisanship and Americanized, fundamentalist and Southern Baptist Christianity. Even as a kid, I listened to Rush Limbaugh on the radio and checked out every book his brother David wrote from the local library. There was always an American flag waving within sight (and I don’t believe that “always” is an exaggeration).

It was a great childhood – I really don’t think I could have asked for any better. But it’s undeniable that in many ways, my childhood was one of intentional and unintentional indoctrination to view conservatism as an ideology that was literally holy and anything “less” than conservatism was less than holy.

As a result, I lived my life until young adulthood believing in the goodness of the wars on terror and drugs, strict immigration control, and legislating morality. I fully believed that the government had every right to determine our lives for us (though I never would have phrased it like that at the time).

First Contact

The first major shock to my statist worldview (again, like many libertarians) came from the former U.S. Congressman from Texas, Ron Paul. I followed the 2012 GOP presidential primary closely and was initially amused and increasingly angered by what Paul said during the debates. I couldn’t believe that someone who I viewed then as entirely unpatriotic could be taken seriously by anyone, let alone be let on a Republican debate stage.

I began digging into Paul out of curiosity – I watched videos of his past speeches and ’08 debate appearances and I read articles he wrote. I was still fully in the conservative statist camp, but I had for the first time in my life began seriously looking at another sort of ideology.

I began digging into Paul out of curiosity – I watched videos of his past speeches and ’08 debate appearances and I read articles he wrote. I was still fully in the conservative statist camp, but I had for the first time in my life began seriously looking at another sort of ideology.

One of the many clips I stumbled across was the “Giuliani Moment”, an exchange from a 2008 debate between Rudy Giuliani and Paul over the motives of the 9/11 terrorists. In this exchange, Paul makes the bold claim that many terrorists hate America because the American military is always bombing and occupying their Middle Eastern and African countries. Giuliani explodes at Paul, saying the claim is absurd, but Paul – rather than backing down – doubled down on his claim that actions have consequences, and encouraged the debate viewers to imagine how they would feel if another country did to America what America does to other countries.

Essentially, Paul was asking them (and me) to have some empathy, to apply the golden rule to foreign policy. In all honesty, at the time I did not value either empathy or the golden rule. Little did I know that all my values were about to be turned upside down.

Finding Christ

In the time period that I begin exposing myself to these initial ideas of a liberty-centered ideology and a worldview built on empathy, I was also going through several other identity transformations, the most meaningful of which involved my faith.

To shorten a long story, I had set out on a personal mission to eradicate Christianity from my life and ended up doing exactly the opposite – I definitely did come to believe many of the teachings I had been raised on as misguided at best, but in return I found something I could finally, truly believe in. I choose to accept Christ and to believe that He actually meant what He said.

To shorten a long story, I had set out on a personal mission to eradicate Christianity from my life and ended up doing exactly the opposite – I definitely did come to believe many of the teachings I had been raised on as misguided at best, but in return I found something I could finally, truly believe in. I choose to accept Christ and to believe that He actually meant what He said.

Among many other things, this meant believing that when Jesus said “turn the other cheek”, He meant it; that when Jesus said “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you”, He meant it; that when Jesus gave the Sermon on the Mount, He meant every word he said. If you choose to look at the teachings of Jesus from this perspective, it’s clear that humans are meant to love each other, unconditionally. I’m not about to claim that this is something I do, but it is something I try to strive for (with varying degrees of success).

Peacemakers

When I came to view unconditional love as an important goal, I could no longer ever view violence in a positive light. Even when violence is used in defense, or in other ways generally accepted by the law and society, it’s still a tragedy. In my mind, I don’t see how I can love one someone unconditionally while at the same time using force against them, in an effort to harm them. I don’t believe that unconditional love and violence can coexist.

For those reasons, my embrace of pacifism came soon after my acceptance of Jesus into my life. I want to be a “peacemaker”, like Jesus asked us all to be.

I don’t want to harm anyone, I don’t want to contribute to the harming of anyone – that’s not what I want my life to be used for. To me, this expands beyond simply physical harm, but mental and emotional harm too. Again, this is an aspiration I fail at constantly – physically I am not a violent person at all (though I admit, I’ve never been truly tested), but I do catch myself saying intentionally mean things, or getting unreasonably defensive. However, I still think it is an important aspiration to keep working towards; it’s something I truly believe.

Unfortunately, the violence that we regularly participate in is not always as obvious as physical violence or cruel words.

The State is Violent

By the time I embraced pacifism I had already shed the majority of my conservative political positions and traded them for more progressive stances that I believed at the time to be more in line with the acts of love Jesus asks of Christians.

Just as I no longer supported physical violence on a personal level, I no longer supported it on government level either (or so I thought). I no longer supported D.C.’s wars, I was adamantly against the drug war and the prosecution of other “vice crimes” with no direct victims, and I became a staunch advocate for ending the death penalty.

Just as I no longer supported physical violence on a personal level, I no longer supported it on government level either (or so I thought). I no longer supported D.C.’s wars, I was adamantly against the drug war and the prosecution of other “vice crimes” with no direct victims, and I became a staunch advocate for ending the death penalty.

At the same time though, I also began believing in policies such as increasing taxes on the rich, breaking up large corporations, and expanding environmental regulations. (This shift in policy alignment again demonstrates the importance of making sure your ideology is backed by solid philosophy – even though I held a conservative ideology for most of my life, since it was an essentially hollow ideology, there was nothing inside me to halt my embrace of progressive economic ideas.)

I didn’t embrace progressivism out of a desire to control people’s lives or to grow the government – I had (as I still believe most progressives do) the best of intentions. I just wanted to help people, and I thought that government institutions, bureaucracy, and taxation/regulation were the best tools to do that. I still held private charities in high regard, but they seemed to be a far less efficient and powerful force than the government for positive change (and in many ways, I still believe that – unfortunately, charity in America is a somewhat atrophied muscle).

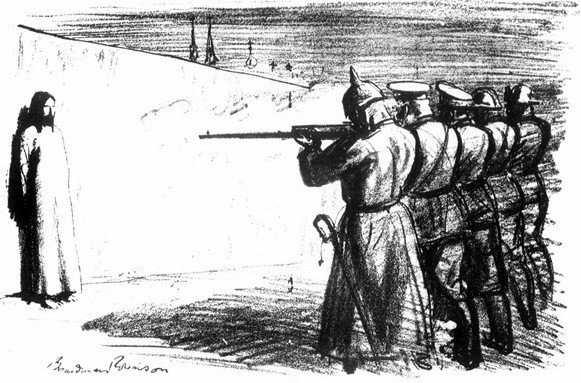

I had to reevaluate my progressive belief system when Eric Garner was brutally murdered.

He was a man – a black man, whom the social justice warrior in me claimed to care so much about – who was robbed, beaten, choked, and killed by agents of the state, the police. And for what? For the crime of not paying taxes to the state. While it didn’t happen instantaneously in my mind, the tragic murder of Eric Garner started me on the path that eventually led to my realization of what a strong, expansive, government – the type of government I had wanted – brings about: inevitable violence.

Anarchism

Eric Garner wasn’t the only one hurt by government laws and policies I had urged on. The more I looked into how these laws and policies were enforced, the more disgusted I became. The sheer number of good people that were undeservingly hurt by law enforcement was appalling. It didn’t matter to me that I wasn’t the one directly committing the violence on these people – by advocating for expanded government, I was part of the cause of their hurt; the police and enforcers were just my all-to-willing, all-to-capable proxies.

This was a reckoning for me – how could I unhypocritically call myself a pacifist, someone unwilling to cause harm, while supporting policies that inevitably harmed people.

The answer was simple: I couldn’t.

After having this revelation, I soon stumbled across Max Weber’s principle that all government authority is rooted in a monopoly on violence. This may seem like an overly-general statement, but I believe it’s true. Think about it: if governments were unable to use force or threats of force, would they even have a tiny fraction of the power they have now? I doubt it.

I have come to believe that all laws are ultimately backed up by violence. If you accept this premise, then you cannot in good conscience support laws that you would be unwilling to use violence yourself to enforce (after all, law enforcement are arguably just the proxies of the citizenry). In my case, as a pacifist, using violence for almost any reason is something I will not take part in, so I cannot in good conscience support the actions of the state that are dependent on violence.

I have come to believe that all laws are ultimately backed up by violence. If you accept this premise, then you cannot in good conscience support laws that you would be unwilling to use violence yourself to enforce (after all, law enforcement are arguably just the proxies of the citizenry). In my case, as a pacifist, using violence for almost any reason is something I will not take part in, so I cannot in good conscience support the actions of the state that are dependent on violence.

I long for a world free of violence, of force, of aggression. I’m tired of individuals (myself included) abusing each other directly, and I’m tired of people using institutions to abuse each other. Wanting a world free of these things means wanting a world free of the state as we know it. It means being an anarchist.

More than the NAP

There is a axiom common in libertarian circles called the Non-Aggression Principle (NAP). This is an incredibly simple concept: aggression is wrong, so it is never moral to initiate violence or force. I believe that in general this is something most rational people can agree to.

(Many libertarians have taken this concept a step further; as I’ve already explained, pacifists reject all violence, not just the initiation of violence. We have a NVP (Non-Violence Principle)).

Neither the NAP nor the NVP are enough though. Simply agreeing to not use force against each other does not a happy, civil society make (though it is a good start). Libertarians need to understand that not all coercion comes from the barrel of a gun and not all tyranny comes from the state. Far to often, libertarians (especially those with a bend to the right) are willing to accept actions that are morally-questionable at best under the guise of “supporting free markets”, or “individual rights”. Unfortunately, our ardent defense of “individual rights” often leads us to forgetting about what is morally right.

Neither the NAP nor the NVP are enough though. Simply agreeing to not use force against each other does not a happy, civil society make (though it is a good start). Libertarians need to understand that not all coercion comes from the barrel of a gun and not all tyranny comes from the state. Far to often, libertarians (especially those with a bend to the right) are willing to accept actions that are morally-questionable at best under the guise of “supporting free markets”, or “individual rights”. Unfortunately, our ardent defense of “individual rights” often leads us to forgetting about what is morally right.

Humanity must take on practices and actions that degrade and diminish anyone. Paying an illegal immigrant $5 an hour might technically be a “voluntary transaction”, but it’s not right. Denying health care to impoverished people may be an “individual right”, but it’s certainly not morally right. Non-aggression and non-violence aren’t enough. Libertarians (and all people of goodwill) need to embrace and practice a principle of non-exploitation.

Pragmatism Works

Now, just because I’m an anarchist doesn’t mean I’m delusional. I’m fully aware that the state is not going away anytime even remotely soon, and probably it never will. I’m fully aware that politics and political action are important parts of the modern world and good can come from them (sometimes, at least).

I’m not one to ever view political action or accomplishments as grand, great goods. It seems to me that even the best political actions are often little more than damage control measures, rectifying to some extent the previous sins of the state. Fortunately though, that “damage control” can sometimes make the lives of literally millions of people better.

Take for example two of the most obvious libertarian wins of the past few decades: the legalization of marijuana and homosexuality. It’s honestly incredible how far these two issues have come in America. Through various state and federal legislative and referendum efforts, millions of people are now free to use and sell marijuana (in an admittedly limited capacity). In almost all legal/public areas of life, the government no longer discriminates against people simply for being homosexual, and they enjoy more personal liberties now that an any time before in America.

Of course, the tragic reality is that millions of Americans still remain imprisoned by cages or felony records due to marijuana, and the shameful treatment of LGBT people by the government (and society) still resonates today. Like I said, most of the progress made with this issues has been damage control to undo previous state injustices. That does not change the fact though, that these advancements were made through political actions and from within the framework of the state. To deny the good that can come from political action is bewildering to me.

If libertarians want to make the world more free through political action, we must be pragmatic. Seeking grand, sweeping, immediate change at the political level is an absolute waste of time, money, and other resources. (Not to mention the fact that a quick and sweeping dismantling of the state would result in little but chaos, more bloodshed, and a reemergent, even larger state.) Change comes incrementally, and often slower than we would like. This is not to say that we should compromise our principles, but simply seek to accomplish as much as is possible and realistic.

In Conclusion,

I’m a Christian, so I’m a pacifist. Due to my pacifism, I’m an anarchist. As an anarchist, my only political option is to be a libertarian. Now, none of that is to say that Christianity, pacifism, or anarchism are necessary facets of libertarianism (though I would argue that some sort of serious anti-violence belief is an inevitable result of Christianity, and anarchism is a necessary part of pure pacifism). Those are just the philosophical elements that make up my worldview which led me to the political ideology of libertarianism.

Likewise, it’s perfectly reasonable to have a pacifist or anarchist philosophy and not practice political action at all, libertarian or otherwise. (In fact, many anarchists make the claim that political action/participation is disqualifying from the label.)

Likewise, it’s perfectly reasonable to have a pacifist or anarchist philosophy and not practice political action at all, libertarian or otherwise. (In fact, many anarchists make the claim that political action/participation is disqualifying from the label.)

Like I said though, everyone’s journey to finding an ideology is different, and whatever your ideology is rarely determines whether you are a good, moral person or not (something else we could all stand to remember a bit more). Personally, I won’t abide by any ideology incompatible with love, peace, and human progress. What about you?