Rethinking Capital Punishment

By Ryan Lindsey

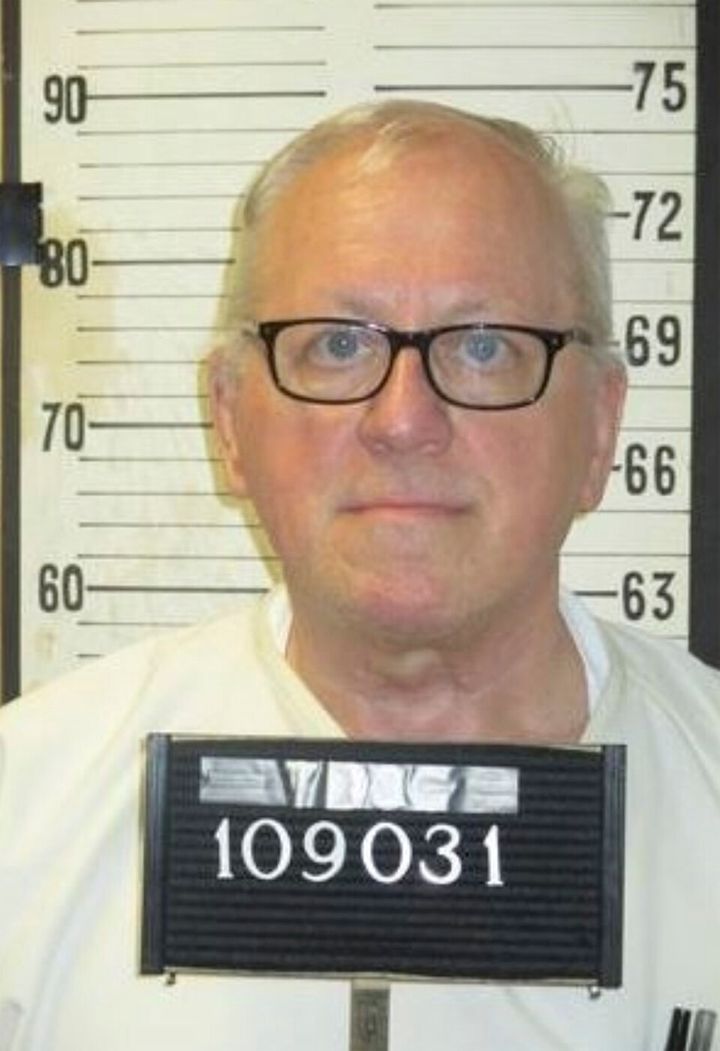

“No more crying there, we are going to see the king.“

The poison had been coursing through Don Johnson’s veins and had almost run it’s course. Within minutes, he would be dead. But still he sang that old hymn, waiting to die and pass on to what was next.

“No more dying there, we are going to see the King“

Don Johnson died.

Of all the ways that we humans can exert power over each other, I would argue that homicide – the taking of life – is the most potent, the most irreversible. Taking life is a completely final act that cannot be undone and erases all the potential (for evil and for good) that the taken life had. Taking life causes catastrophe for those close to the victim and the perpetrator, it results in a massive crater on the fabric of communities.

I’d venture to say that the overwhelming majority of Americans, of all political and ideological persuasions, believe that killing in self-defense is morally permissible. Many probably believe that some cases of preemptive killing are justified. But very, very few believe (or at least would admit that they believe) that killing unarmed, helpless, restrained people is a tolerable practice. Yet when it comes to the death penalty, many of us make an exception to this rule. We accept that state-sanctioned and performed revenge-based killings are not only moral, but necessary.

I think that this is an idea we should all run away from, as fast as we can.

Killing the Innocent

At the time I’m writing this, America has executed 1,500 prisoners since the death penalty was resumed in 1977. According to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), 155 people have been exonerated from death row since 1977. This means that for every ten people on death row who are executed, one has been proven innocent. While I am grateful that 155 lives were saved, I can’t help but worry that many more of those who were killed were innocent (or at least, not guilty of the heinous crimes they were killed for).

The stories of the death row inmates who were exonerated are full of civil liberties violations, laziness and corruption in the courts, and a whole lot of chance. Almost all of those who were exonerated were saved due to an outside benefactor stepping in on their behalf – that’s a luxury many prisoners sentenced to die are not awarded. Let’s take a look at a few of these exoneration cases:

Jerry Banks was exonerated in 1980 after being convicted of two counts of murder in 1975. During his initial trial, the state purposefully withheld evidence (Banks v. State, 218 S.E.2d 851 (GA. 1975)). Once this was discovered (by chance), his conviction was overturned. His wife divorced him shortly after his release and Banks killed himself.

James Richardson was exonerated in 1989 after being convicted of killing all of his seven children in 1968. During his initial trial, the prosecution lied about Richardson’s childrens’ life insurance policies, ignored other more likely suspects, withheld evidence, and used perjured testimonies (Richardson v. State, 546 So.2d 1037 (FL. 1989)). His trial received attention once two journalists began looking into it and raising questions.

Adolph Munson was exonerated in 1995 after being convicted of first degree murder and kidnapping in 1985. During his trial, the prosecution withheld a large amount of exculpatory evidence from Munson and his lawyer (Oklahoma v. Munson, 886 P.2d 999 (Okla. Crim. App. 1994)). Munson was released after two appeals and one of the experts who presented “evidence” at his original trial was stripped of his license.

Isiah McCoy was exonerated in 2017 after being convicted of first degree murder in 2012. During his trial, the prosecution manipulated and intimidated both McCoy and the jury, and lied to the judge (McCoy v. State, Nos 558 & 595 (DE 2012)). He was exonerated once the prosecutor’s misconduct was revealed by chance. The prosecutor was only temporarily suspended.

These are just four of examples of death row exonerations, but I can guarantee you this: almost all of the 155 death row exonerations since 1977 are filled with the same amount (or more) or prosecutor misconduct, corruption, and incompetence. Almost all of the 155 death row exonerations occurred only because an outsider stepped in to help or asked questions or bothered to take a second look at a trial. It’s abundantly common for criminal trials to be mishandled. It’s not nearly as common for those mishandlings to ever be made public knowledge.

It boils down to this: you can support having a death penalty or you can oppose the government killing innocent/undeserving people, but you can’t do both. The death penalty has killed innocent people and it will continue to do so. The only way to stop the state from using capital punishment to kill innocents is to abolish it – no amount of reform or extra precautions will make the death penalty process 100% foolproof; government is simply to corrupt and incompetent to be trusted with this awful power (this is a truth that should be easy to accept for both libertarians and small-government conservatives).

To support the death penalty is to believe that a certain amount of innocent death is an acceptable price to pay for what is essentially a revenge killing. This is an extremely, dangerously out-of-control utilitarian idea. It is also an idea that is completely devoid of any sense of empathy.

If you happen to believe that inevitable innocent death is an acceptable cost to maintain a state death penalty, then ask yourself this: would you feel the same way if you were falsely convicted and on death row?

I doubt it.

An Extension of White Supremacy

It’s well-known that those who are poor, black, or generally outcasted from society are tread upon especially hard by the American criminal justice system. Appeals and the thousands of hours of manpower and research that go into them are expensive, and most death row inmates can’t afford them. Aside from a benevolent benefactor of some sort (which is no sure thing) a successful appeal is nothing but a dream to many of those sentenced to die.

Not only does the death penalty unfairly affect the poor, but it is also used disproportionately against black Americans. According the Equal Justice Initiative based in Montgomery, Alabama, 13% of the American population is black, but 42% of death row inmates are black and 34% of those executed are black. Additionally, over 80% of executions involve white victims, although whites only make up around 50% of murder victims. It’s no coincidence that in the late 1800s and early 1900s as lynching decreased that executions increased. It’s also worth noting (as the Connecticut Supreme Court pointed out when they banned capital punishment in their state in 2015) that “the 13 states that comprised the Confederacy have carried out more than 75% of the nation’s executions over the last four decades [since the death penalty was reactivated in the U.S.].”

It’s not always popular to point out that racism still haunts American society and civic institutions, but I earnestly believe it’s the truth and it’s a truth I wish more libertarians and liberals would embrace. If you don’t believe me, take a minute to examine the 1987 Supreme Court Case McCleskey v. Kemp. McCleskey was a black man who was accused and convicted of killing a white police office in Georgia and was sentenced to death. McCleskey and his lawyer argued in a writ of habeas corpus that statistical studies showed that Georgia’s application of the death penalty depended heavily on the race of the accused as well as the race of the victim. Multiple studies showed that black men who killed white victims are far more likely to receive the death penalty than other racial combinations of perpetrators and victims.

The Rehnquist Court considered those studies and, surprisingly, agreed with the studies findings – they concurred with McCleskey that in Georgie, and likely most of the U.S., that race played a significant role in the application of the death penalty. Unfortunately, they went on to describe this racial bias as “an inevitable part of our criminal justice system.” Even the United States Supreme Court recognizes the extreme racial bias in the criminal justice system as a whole and in capital punishment in particular. And not only did they recognize it, they labeled it as acceptable. In a 5-4 decision, the court decided against McCleskey.

The Rehnquist Court considered those studies and, surprisingly, agreed with the studies findings – they concurred with McCleskey that in Georgie, and likely most of the U.S., that race played a significant role in the application of the death penalty. Unfortunately, they went on to describe this racial bias as “an inevitable part of our criminal justice system.” Even the United States Supreme Court recognizes the extreme racial bias in the criminal justice system as a whole and in capital punishment in particular. And not only did they recognize it, they labeled it as acceptable. In a 5-4 decision, the court decided against McCleskey.

Even if you are able to support capital punishment in a theoretical sense, seeing how much the actual practice of it is distorted by class and history should give you pause. Racial angst is on the rise, and the unequal application of the death penalty is one of the many reasons why. I’m not going to make the foolish claim that abolishing the death penalty would solve America’s racial disparities, but I can’t help but believe that it would be a definite step in the right direction to racial reconciliation.

A Better Way Forward

When the death penalty is stripped of all the legalese and conservative rationalizations all that’s left is revenge killing, plain and simple. I for one think that revenge is sorry substitute for justice and has no place in our civic institutions, and I’d like to think that most you would agree.

I am convinced that the death penalty hurts everyone involved – those sentenced to die, those who do the sentencing, the families of victims, the executioners, etc. Thankfully, I believe there’s a better way.

What if our system of justice went deeper and was more meaningful and satisfying than “an eye for eye”? What if the focus was on making things right with both victims and perpetrators, rather than on making sure some people get “what they deserve”?

I’m sure many of you are at least vaguely familiar with this idea of restorative justice. American criminologist Howard Zehr defines restorative justice as “a process to involve, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense and to collectively identify and address harms, needs, and obligations, in order to heal and put things as right as possible.”

When our current system asks What laws were broken?; By who?; and What do they deserve?, restorative justice asks Who was hurt?; What do they need?; and Who is obligated to address these needs?.

Restorative justice has a place in even the most heinous of circumstances. Take for example the Rwanda genocide – the men responsible for the genocide were tasked with rebuilding the country; you can still them working to fix roads and farms, armed with shovels and other tools. (One could say that they literally beat their swords into plows.) Rather than facing death (which I’m sure many would argue they deserved) they work to restore their home to what it was before. They aren’t getting off easy by any means – they’re spending the rest of their lives undoing the damage they contributed to and facing their victims. I would argue that this “punishment” requires more from the perpetrators and gives back more to the victims than capital punishment ever could.

If restorative justice can work to heal the wounds of genocide, then surly it can be used to heal the wounds of murder. There are countless stories of the families of victims eventually writing and talking with, meeting, and even befriending the individual who killed their loved one – they work together to heal each other, realizing that most criminals are victims themselves and not all that different from us “respectable folk”. There are far too many of these stories to recount here, and they’re too beautiful to only give a brief summary, but I have to ask anyone reading this to please take fifteen minutes or so to at least look up the story of Hector and Susie Black – their story touches me every time I read or listen to it.

One Last Thing

The final story I want to tell is that of Don Johnson, who was executed in a Tennessee prison this past May. Johnson murdered his wife, Connie Johnson, in 1984 and was soon convicted and sentenced to death. In prison, Don became a Christian and soon became respected and befriended by many of his fellow prisoners and even a few of the prison guards. He regretted his actions tremendously and dedicated the rest of his life to serving those imprisoned with him however he could. Johnson was denied clemency by Governor Bill Lee multiple times. He asked for the money that would have been spent on his last meal to go towards feeding the homeless (a request that was also denied). As he was led into the execution chamber, he forgave those who were killing him and asked for forgiveness again from all those he had hurt during his life. He sang hymns until he passed out and died.

(Note: the information about Johnson’s final days and minutes is from one of Johnson’s close friends, Shane Claiborne, who has written extensively about ending the death penalty in his book Executing Grace.)

Don Johnson did something horrible, but he clearly wasn’t beyond redemption and good was coming from his life. When you think about the death penalty from now on, I’d like you to think about Don’s final days. Think about all those who are executed as people first and as criminals second (or not at all). Some of the names of those executed in America are in this article, in the lines between columns.

The idea of restorative justice isn’t easy – it could require a tremendous amount of imagination, compassion, and empathy in many cases. But I think it’s an idea worth striving for, worth realizing. It just might help us save our humanity.

Ryan Lindsey is the founder and editor of WAL Reader, as well as a pen-pal to death row inmates through Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty.